The Four Lenses Strategic Framework

The Four Lenses Strategic FrameworkPurpose

PurposeThis paper aims to move beyond stories and definitions by presenting practitioners with a conceptual framework—as rudimentary as it may be in its first version—to inform and inspire new thinking about social enterprise performance and impart strategy and management resources to help practitioners achieve high performing social enterprises.

The paper’s larger audacious goal is to engage practitioners, academics, donors, and other sympathizers in a debate that will move toward developing social enterprise methodologies and best practice. In presenting this foundational social enterprise performance framework we fully expect it to change, evolving both in content and form, while also inciting any number of tangential or niche frameworks and methodologies. And so begins the effort toward founding common performance parameters for social enterprise from which to evolve a methodology…

The paper is a sequel to the Social Enterprise Typology, a paper that elaborates the rich mosaic of highly differentiated and creative examples of social enterprise, and by doing so, served as a precursor to organizing these diverse approaches and strategies into a common framework.

Audience

For practitioners the frameworks are intended as management and planning tools: to help them plan strategically; to diagnose and analyze problems; to set objectives and measure outcomes; and to leverage synergies and manage tensions within a social enterprise in order to optimize organizational performance. For academics the frameworks offer fodder for debate and critical thinking, and aims to provide early theoretical constructs toward building a social enterprise methodology. For donors, the framework can be used as a performance measurement and monitoring tool, and for consultants to assist technical input.

This first version is made available as part of the www.4lenses.org website and practitioners and others are invited to add their comments, share their examples, challenge our assertions, and so on.

We fully expect the framework to evolve as more practitioners use it. As they do, revisions and updates will be posted along with new field tools and examples.

Terminology and Definitions in the Context of this Paper

Terminology and Definitions in the Context of this PaperThe following definitions are intended to clarify the meanings of terms used in this paper. They are not meant to integrate all meanings that might be given to these terms in other contexts, and their lack of concurrence with other meanings should not be construed as an objection to their use.

Social enterprise - socially-oriented venture (nonprofit/for-profit or hybrid) created to solve a social problem or market failure through entrepreneurial private sector approaches that increase effectiveness and sustainability while ultimately creating social benefit or change.1 For more information, refer to the Social Enterprise Typology.

Social enterprise methodology – the methods and organizing principles underlying the study of social enterprise.

Social sector – the part of the economy characterized by organizations whose goals and responsibilities are the maintenance and development of the common/public good through the acquisition, transformation and allocation of public property, goods and services.

Private sector – the part of the economy characterized by businesses whose goals and responsibilities are the maintenance and development of private wealth through the acquisition, transformation and trading of personal property. In most legal environments, they can adopt generic “for-profit” legal structures meant to regulate ownership rights and responsibilities among stockholders and creditors as well as general liability.

Social impact – the addition, preservation, or reduction of value for a common good and/or target beneficiary. (In social sector literature, social impact is mainly used to connote a positive benefit.)

Business practices – the methods by which private-sector businesses intervene through market mechanisms in order to shape market forces to their advantage.

Market Failure – the failure of a more or less idealized system of price-market institutions to sustain desirable activities (broadly defined) to cover consumption as well as production. The desirability of an activity is evaluated relative to the solution of values of some explicit or implied maximum welfare problem.2 In social enterprise literature, “social market failure” is used to describe a malfunction of government to render social services (i.e. health, education, utilities, transportation, etc.).

Executive Summary

Executive SummaryThe Four Lenses Strategic Framework is not meant to be authoritative nor static. It is meant to support a practitioner-driven debate to further define common components of the social enterprise methodology. In the context of this paper social enterprise is defined as: “a socially-oriented venture (nonprofit/for-profit or hybrid) created to solve a social problem or market failure through entrepreneurial private sector approaches that increase organizational effectiveness and sustainability while ultimately creating social benefit or change.1 ” It follows that social enterprise methodology is comprised of “the methods and organizing principles underlying the study of social enterprise.”

At the core of the framework is the concept of sustainable social impact, the end goal which drives the social entrepreneur. Here, we intentionally do not give a comprehensive definition of the concept and set no boundaries.2 Instead we focus on the concept of sustainable social impact and identify four common themes—we call them performance criteria—that appear to propel many social enterprise practitioners in their pursuits:

- Depth of impact—the drive to develop and implement solutions that address the root causes of social problems in order to achieve deeper, more lasting social impact.

- Blended value—the drive to develop and implement blended value creation models that make economic wealth creation and social value creation interdependent, so that eventually one cannot exist without the other.

- Efficiency—the drive to develop and implement processes and technologies to achieve increased efficiency, so that more can always be done with a set level of resources.

- Adaptability—the drive to develop and implement solutions that are more flexible and adaptable, so that lasting social impact can be realized in ever-changing and unstable environments.

The four performance criteria act as references around which social enterprise practices can be identified, organized, compared, and possibly formalized into methodological components. In doing so, the framework serves to identify, around the four performance criteria, social enterprise practices that seek to leverage private sector strengths while addressing private sector limitations and market failures.

Upon closer study of the performance criteria, the framework then offers the following analysis: behind each performance criteria lies a set of activities that can be grouped in four strategic areas—we call them strategic lenses:

- Stakeholder Engagement—activities related to involving all who have a role to play in addressing the social problem toward more sustainable social impact.

- Resource Mobilization—activities related to assembling and putting into action the necessary means toward more sustainable social impact.

- Knowledge Development—activities related to improving the quality, relevance and appropriateness of information and processes toward more sustainable social impact.

- Culture Management—activities related to guiding behaviors and mindsets toward more sustainable social impact.

While each performance criteria relates directly to each of the lenses, the extent to which one impacts the other varies. For example, resource mobilization is the most critical strategic lens for issues pertaining to generating blended value--but if all types of resources (i.e. human, social, physical, natural, and financial) are not fully mobilized and managed, then the social enterprise will invariably miss opportunities to maximize economic and social value creation. Resource mobilization is also important toward achieving depth of impact but to a lesser extent—a social enterprise could conceivably create impact without mobilizing all its potential resources. Thus, each performance criteria has a primary lens, although to get the most out of performance, each criterion should be carefully filtered through every strategic lens.

Once performance criteria and critical strategic areas common to social sector organizations are identified, the framework can be used to examine the interplay between strategic actions and performance, and how the two together, or in opposition, lead to sustainable social impact. When performance criteria are refracted through the strategic lenses, interdependent relationships between strategic action and performance outcome become evident. Relationships between strategic actions may be synergistic and thus leveraged to have a greater positive effect on performance, or by contrast, strategic actions may underscore inherent tensions within the lenses that must be managed to achieve the desired performance outcome.

This paper aims to move beyond stories and definitions to structure social enterprise performance. Its task is to inform and inspire new thinking about formalizing a performance methodology to help practitioners achieve efficient, adaptive, strategically-minded organizations capable of simultaneously creating economic wealth and social value and addressing root causes of social problems in order to achieve deep, lasting social impact.

- 1Alter, Kim, Social Enterprise Definition, Virtue Ventures, 2006.

- 2In our view, sustainable social impact is characterized by unique combination of the vision and goals of the social entrepreneur, the nature of the social problem and circumstances surrounding it, and the chosen social enterprise solution. and thus must be defined in its own context. Generically, sustainable social impact is the resolution of the social problem or market failure.

Part 1: Introducing Social Enterprise Performance

Part 1: Introducing Social Enterprise PerformanceOverview and Rationale

Overview and RationaleAsk any self-respecting social entrepreneur why they do what they do, and they will tell you passionately about a social problem and how they are working to solve it. Most achieved a moment of clarity when they recognized an injustice and were compelled to take action. In tackling the social problems, their approaches are as wildly different as the problems themselves, yet our research and experience tells us that social entrepreneurs’ motivation is ubiquitous—to make sustainable social impact.

To this end, social entrepreneurs are obsessed with how well they achieve social impact. Regrettably, little attention has been given to examining performance in social enterprise methodology; instead numerous pages have been written on capturing how much social impact social entrepreneurs achieve. At first glance these perspectives appear identical, and they are indeed interdependent: the first stresses organizational performance, which then produces the second, external impact (measuring social impact metrics).1 Our assertion is that by enabling social entrepreneurs to assess and improve how well they achieve social impact they can in turn improve their performance, and increase how much impact they achieve.

We begin with a bold thesis: social enterprise is a paradigm for social organizations to achieve high performance.

In this paper we define social enterprise as: “socially-oriented venture (nonprofit/for-profit or hybrid)2 created to solve a social problem or market failure through entrepreneurial private sector approaches that increase organizational effectiveness and sustainability while ultimately creating social benefit or change.”3

We define high performance organizations as “efficient, adaptive, strategically-minded organizations capable of simultaneously creating economic wealth and social value and addressing root causes of social problems in order to achieve deep, lasting social impact.”

However, at the time of this writing there is a dearth of tangible materials and tools devoted to helping social enterprise practitioners understand and improve their performance—do what they do better. Instead, social enterprise literature is rife with definitions and chronicles of social sector leaders and their endeavors. The power of inspirational stories to motivate aspiring social entrepreneurs to implement their ideas should not be underestimated; however, analyzing and chronicling best practices is required to understand social enterprise performance, ergo develop social enterprise methodology.

Social enterprise methodology gains to date underscore three narrowly-focused schools of thought:4

- the Social Entrepreneur Approach, which supports leadership development of the practitioner;

- the Funding Approach, which advocates earned income as a means to fund social projects and organizations; and

- the Program Approach, which uses commercial activities to execute social programs (i.e. micro-credit).

All three approaches have merit, yet neither alone nor together do they go far enough for the practitioner who is interested in mitigating a social problem. Money is motivating only in that it is a necessary means to finance costs related to solving a social problem. Strong leadership is essential to the success of any social enterprise, yet does nothing to address pragmatic questions related to institutionalization or capacity building. Finally, employing business activities is attractive only if doing so generates greater social value.

Social enterprise lies at the nexus of management science and social science, and therefore its practices should be drawn from and inspired by multiple disciplines such as business administration, social work, geography, policy studies, anthropology and economics. Social problems, too, are complex and often require multifaceted tactics to untangle their causes and effects. Thus, any comprehensive social enterprise methodology must take a holistic view of the social enterprise and integrate and build on current schools of thought—leadership, funding and program.

An integrated methodology requires that a complex network of internal systems function individually as well as interdependently to achieve a healthy whole. Diagnosing “symptoms” of poor social enterprise performance such as the inability to draft a strategic plan, high staff turnover, improper financial management, mission discord, dissatisfied clients, a poorly functioning board, etc. may indicate weaknesses in one functional area, whole systems, or institution-wide. Correcting problems may be isolated events or require comprehensive change management; either way changes in one area or many has an inherent impact on the performance of the social enterprise, for better, for worse or both concurrently. Social enterprise performance is dependent on the interrelationship between money, people, community, resources, capacity, leaders, values, knowledge, culture, acumen, and vision, etc. and how these aspects work together, or in opposition, toward achieving the end goal of sustainable social impact. Thus, achieving a high performing social enterprise is like a steady fitness regime that requires enduring vigilance, not only to remedy problems, but to strengthen capacity and maintain general health.

- 1The relationship is illustrated with a logic framework: organizational outcomes are the result of activities that lead to measurable outputs and subsequently organizational change, the cumulative effect is impact.

- 2Social enterprise is agnostic about legal form, which is usually dictated by governing laws in the countries where they operate.

- 3Alter, Kim, Social Enterprise Definition, Virtue Ventures, 2006.

- 4Alter, Kim and Vincent Dawans, “The Integrated Approach to Social Entrepreneurship: Building High Performance Organizations,” Social Enterprise Reporter, April 2006.

Framework Purpose

Framework PurposeSocial enterprise has been touted as the answer to achieving performance gains in the third sector, yet as a field it has been slow to develop its core methodological components. The purpose of this framework is to support the social enterprise community by developing an integrated methodology, one that goes beyond splintered factions and works to unite social enterprise around common challenges and performance criteria, thereby furthering the development of social enterprise as an established field and a means for achieving sustainable social impact.

Social enterprise achieves social impact by creating social, economic, and environmental value. Using a market-based approach, social enterprise incorporates commercial forms of revenue generation (and thus creates economic value) as a means to accomplish its social mission (and thus creates social value and/or environmental value);1 the combination of these results is a “blended value” outcome. Simply put, it is difficult to dissect value produced by the social enterprise and assign it to discrete activities because value production is a function of the interdependent nature of all social enterprise activities. For example, the social value of wealth generated by a successful microfinance institution (MFI) can be directly correlated to the economic value created to keep it afloat: the greater the number of productive loans disbursed, the greater the benefit to poor entrepreneurs, and the greater the amount of interest collected to sustain the MFI.

In the social enterprise, the means by which value can be created are as diverse as the social enterprises themselves. For instance, social value can be achieved through any or all of the following modalities: a direct result of executing the business; ancillary social programs; social services embedded in the social enterprise model; management and/or governance philosophy or processes; procurement of supplies and raw materials; strategic partnerships; and socially and/or environmentally responsible policies. To complicate, trade-offs occur whereby one type of value is compromised, curtailed, or forsaken to achieve another type of value. Most often this relates to economic value at the cost of social or environmental value to ensure the social enterprise’s survival. For instance, microfinance institutions went upmarket, making larger and higher margin loans to the “less poor” as a means to commercialize. The concession was reduced group loans to the “poorest of the poor,” while the benefit was being a going concern that could lend to many more poor people over time. The goal is to be strategically intentional about where and how to create maximum value and to view value creation as a holistic outcome of social enterprise performance.

Questions we seek to answer:

- How is performance defined and measured in social enterprise?

- What do we mean by ‘integrated methodology’?

- How can integration lead to higher performance?

- 1Social enterprise may add environmental value by employing environmental sustainable practices in its activities, or in the case of an environmental social enterprise—e.g., Nature Conservancy—environmental benefits are baked into the organization’s mission and integrated with its social programs.

Structure

StructureFirst, we start by framing performance in the context of sustainable social impact, this being the ultimate goal of any social enterprise. In doing so, we avoid attempting to arrive at a common definition of ‘sustainability,’1 but instead focus on key characteristics exhibited by successful social sector organizations, namely their commitment to achieving (1) deeper social impact, (2) blended socio-economic value, (3) increased efficiency and (4) greater adaptability. We further demonstrate that the lack of these characteristics would negate any pretense of sustainability (although we certainly do not imply that their existence is all there is to sustainability).

We then apply these performance criteria to the social enterprise methodology, describing how social enterprise practitioners have addressed the challenges common to all social sector organizations along the four performance criteria.

Second, we make the case for an integrated social enterprise methodology. We start by demonstrating that social sector organizations, regardless of their performance, face common challenges in four strategic areas—we call them strategic lenses: how they engage their stakeholders, mobilize their resources, develop their knowledge, and manage their culture. We then conclude that each strategic lens has a role to play in each of the four performance criteria, potentially creating a complex series of synergies and tensions calling for an integrated approach across all four strategic areas to achieve the organization’s performance objectives.

Next, we conduct an analysis of how social enterprise practices seen through these four strategic lenses can potentially impact organizational performance. More importantly, we seek to show the integrative relationship between key performance criteria and social enterprise practices seen through the four lenses—a shift in organizational practice seen through any of the strategic lenses will impact (positively or negatively) the organization’s performance across the key criteria. Thus, we combine key performance criteria with the four strategic lenses to arrive at an integrated framework that we hope will further the development of social enterprise methodology as a means for achieving optimal performance in social sector organizations.

- 1This is an important ongoing debate but not the purpose of this framework.

Part 2: Framing Performance

Part 2: Framing PerformancePremise

PremiseThe performance of a social sector organization is ultimately measured by its ability to create and sustain social impact.1

Sustainable Social Impact

“Sustainable social impact,” meaning enduring social impact, is a frequently used term in social enterprise literature and jargon. In some camps, creating sustainable impact is linked to institutional and financial sustainability; the underlying assumption is that if an organization exists in perpetuity its impact is sustained. In the context of this paper, however, and for the purpose of informing social enterprise methodology, sustainable impact, has everything do with solving a social problem or market failure. In other words, when a social problem or market failure is resolved, continued impact is achieved because the problem ceases to exist.

Does that mean that the concept of creating a sustainable institution is in conflict with solving a social problem? Not necessarily. In most cases solving social problems is a long-term proposition requiring systemic change that can take generations to realize. Working toward the resolution of a social problem may require rendering ongoing social services through a sustainable institution over many, many years. In many cases the social enterprise becomes a permanent fixture, a “third sector” institution in the landscape of private, state and civil society. Nonetheless, it does mean that a social enterprise must plan formal exits or reinvent itself to address new problems as old ones fall away. Here, it is relevant to consider Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,2 and how the nature of human need evolved: as “base” physiological and safety needs are met, a person moves up the pyramid toward self-actualization. Hence, once one problem is solved, another one often surfaces, so new opportunities continue to present themselves.

Beyond Financial Sustainability

“Private sector practices” in social enterprise are borrowed from the commercial business and pertain to financial profit-making activities. However, for a social enterprise whose goals are to sustain social impact as well as its own existence, sustainability is a good deal more complex than simply earning money. Also, lest we not forget, one role of the social sector is to mitigate or undo harm to society, the environment, and its people, some of which is the result of unsustainable behaviors of the private sector. To fully appreciate sustainability in the context of the social enterprise, one must consider the three interrelated aspects that enable a social enterprise to become self-sustaining: financial sustainability (the ability to generate income to cover expenses), institutional sustainability (organizational capacity to execute and compete in the market) and sustainable environmental practices (the use of renewable materials, energy and processes that do not ravage the environment). A social enterprise combines at least financial and institutional forms of sustainability, and often environmental sustainability, to create and sustain social impact.

Identifying Common Performance Criteria

Identifying Common Performance CriteriaThe challenge in creating a common performance framework is that both the concepts of social impact and sustainability are hotly debated and highly subjective.

Hence, in creating a common framework, we have chosen to focus on a set of common criteria that can be simply demonstrated and accepted as being essential to sustainable social impact creation, without pretending to define the full scope of ‘sustainable social impact.’

The framework establishes four common performance criteria that lead to increased sustainability:

The framework establishes four common performance criteria that lead to increased sustainability:

Depth of Impact. How effective is the organization at addressing the underlying causes of the social problem? There is no sustainability without deep, lasting impact—solving (not palliating) the social problem should be the end goal.

Blended Value. How effective is the organization at making economic wealth creation and social value creation truly interdependent, so that eventually one cannot exist without the other? There is no sustainability without blended value creation because it is not viable to maintain activities that generate a value deficit.1

Efficiency. How effective is the organization at systematically striving to do more with less? There is no sustainability without efficiency because waste leads to a vicious cycle of resource attrition.

Adaptability. How effective is the organization at adapting to changing conditions? There is no sustainability without adaptability because the inability to negotiate threats and seize opportunities leads to exhaustion and extinction.

We can think of these four performance criteria like the central pieces of a puzzle—if one is missing, we will never arrive at a full picture of sustainability. That said, we do not assume that these performance criteria are all there is to achieving sustainability—our focus has been to identify the common pieces at this stage of development of the social enterprise field.

- 1We use the term blended value here as defined by Jed Emerson: “What the Blended Value Proposition states is that all organizations, whether for-profit or not, create value that consists of economic, social and environmental value components—and that investors (whether market-rate, charitable or some mix of the two) simultaneously generate all three forms of value through providing capital to organizations. The outcome of all this activity is value creation and that value is itself non-divisible and, therefore, a blend of these three elements.” Read more about blended value at www.blendedvalue.org

Applying the Performance Criteria to the Social Enterprise Methodology

Applying the Performance Criteria to the Social Enterprise MethodologyTo be relevant as a methodology for social sector practitioners, social enterprise must address the challenges common to all social sector organizations, while offering novel approaches to addressing these challenges.1

At the core of social enterprise methodology lies a simple observation: private sector markets—like it or not—are predominant worldwide, massively overshadowing public sector markets. At the same time, many social sector challenges can be demonstrably related to the inclination of private sector markets to provide for the short-term needs of a few rather than for the long-term common good—particularly when the two are not deemed compatible.

The social enterprise methodology differentiates itself in the way it seeks to associate social sector challenges and private sector limitations. It addresses both concurrently by leveraging the strengths of private sector markets (as exemplified by the business methodology) to achieve social gain.2 The beauty of social enterprise is that commuting business practices to effect social change offers so much more possibility than just money.3 Social enterprise methodology harnesses the power of the private sector by actively engaging in the market and strategically employing market mechanisms in decision-making to solve social problems and generate value for the greater good. Other methodology tenets include operating the social enterprise with the financial discipline, innovation and determination characteristic of private business, which promote savvy survivalist behavior time-tested in markets.

| Address social sector challenges… | …by leveraging private sector strengths while addressing its limitations. | |

|---|---|---|

| Depth of Impact: How effectively do we address the social problem? |

|

|

| Blended Value: How effective are we at integrating social and economic value creation? |

|

|

| Efficiency: Do we systematically strive to do more with less? |

|

|

| Adaptability: Are we willing and able to respond to changing conditions? |

|

|

- 1We are not implying that being novel automatically makes you better; instead we are saying that to be relevant, a new methodology obviously has to bring something new; whether it performs better has to be judged on, well, how it performs! This seems rather obvious but important to avoid falling in the trap of innovation for the sake of innovation.

- 2This "fighting-fire-with-fire" aspect is probably what makes the social enterprise methodology both effective and hazardous at the same time.

- 3Alter, Kim. “Social Enterprise Models and Their Mission Relationships,” in Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Innovation. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Part 3: The Case for Integration

Part 3: The Case for IntegrationIdentifying Common Strategic Lenses

Identifying Common Strategic LensesWe have seen that performance (good, bad and neutral) can be traced to a series of common challenges relating to the four performance criteria outlined above.

Although the particulars of these challenges are naturally wide ranging, depending on the nature of the social problem and the operating environment, most challenges call for actions in four common strategic areas: Stakeholder Engagement, Resource Mobilization, Knowledge Development, and Culture Management.

These four central themes—we call strategic lenses—highlight a series of strategic questions common to all social sector organizations.

| Strategic Lens | Central Theme | Core Strategic Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement | A stakeholder is anyone who has a role to play in addressing the social problem (i.e. community, clients, donors, staff/ management, board, environment, public, etc.). |

|

| Resource Mobilization | Resources can be:

|

|

| Knowledge Development | Knowledge is the combination of information (content, results from research, data) and processes (methodologies, systems, techniques, procedures). |

|

| Culture Management | Culture results from the combination of the many belief systems and mindsets found among stakeholder groups. |

|

Social Enterprise: Assessing and Delivering Performance through the Four Strategic Lenses

Social Enterprise: Assessing and Delivering Performance through the Four Strategic LensesNow that we have identified performance criteria and critical strategic areas common to social sector organizations, we can start examining the interplay between strategic actions and performance, and how the two together can lead to sustainable social impact. The construct of strategic questions related to each strategic lens and cross-referenced with performance questions can be used to create a diagnostic tool to assess social enterprise performance.

Performance assessment through Four Strategic Lenses highlights unrealized opportunities to increase performance, indicates weaknesses and pinpoints conflicts that may detract from achieving performance objectives. Once social enterprises performance is assessed, its leaders can decide which strategic actions should be pursued to enhance or improve performance in pursuit of sustainable social impact.

Assessment can be conducted formally and comprehensively and used to inform periodic strategic planning with ongoing performance monitoring . However, the true strength of the Four Lenses Framework to deliver high performance lies in its potential to be incorporated into daily social enterprise management practice and decision making. Constant vigilance, rather than episodic attention, is required for a social enterprise to attain and maintain a sustainable social impact.

The chart above and table following illustrates the relationships between the strategic lenses and performance criteria, and therefore the synergies and tensions within the lenses themselves. Its important to note that social sector organizations are dynamic. Although the depiction in the chart gives each of the lenses equal weight, weights can shift depending on the relative importance of what is going on within the organization or how the organization is affected by what is going on in the external environment. Practitioners may concentrate on improving the social enterprise performance of one lens given the urgency or timeliness of internal factors (deficit, new leadership, stakeholder resistance, etc) or external factors (emergent competition, partnership opportunity, etc.).

The Four Lenses and their relationship to performance function like clockworks: adjustments in one lens to improve performance creates the need for tinkering in other lenses. As suggested by current social enterprise theory, a focus on one dimension of performance (historically these were leadership, funding, program) in and of itself does not achieve sustainable social impact. Social enterprise performance objectives are attained by comprehensive management of all strategic lenses (though one or more may take priority at a particular time) as well as the interplay between the lenses. In short, high performance cannot be achieved if actions and decision making in one or more of the strategic lenses are neglected.

| Performance Criteria | Primary lens through which performance is delivered… | Secondary lenses further enhancing or hindering performance… | Depth of Impact | How successful are we at engaging all stakeholders deeply and durably? | How do our culture, resources and knowledge support (or hinder) a deeper stakeholder engagement? |

|---|---|---|

| Blended Value | How successful are we at mobilizing resources in an integrated, viable and renewable manner? | How do our knowledge, stakeholders and culture support (or hinder) viable resource mobilization? |

| Efficiency | How successful are we at developing knowledge that leads to more appropriate processes? | How do our resources, culture and stakeholders support (or hinder) the development of appropriate processes? |

| Adaptability | How successful are we at creating a culture that supports initiative and reduces resistance to change? | How do our stakeholders knowledge and resources support (or hinder) a culture of change and initiative? |

The Rubik's Pyramid Challenge

The Rubik's Pyramid ChallengeThe framework offers one explanation for why sustainable social impact appears much easier to achieve than it actually is! Although it looks like a simple puzzle when we sign up for it, achieving sustainable social impact actually requires solving a Rubik’s Pyramid.

From a simple puzzle…

… to a Rubik’s pyramid!

In a Rubik's Pyramid, each of the four faces is covered by nine small triangles, divided among four solid colors. A pivot mechanism enables each face to turn independently, thus mixing up the colors. For the puzzle to be solved, each face must be a solid color.

The four lenses are like the side of the pyramid: trying to “solve” one without the others is counter-productive. Instead, all four need to be addressed in an integrated manner to solve the puzzle.

Part 4: Leveraging Synergies and Managing Tensions

Part 4: Leveraging Synergies and Managing TensionsThe following table illustrates how each performance criteria fits within the four strategic lenses, and describes sample activities that demonstrate the interplay of strategic actions with performance outcomes.

While each performance criteria relates directly to each of the lenses, the extent to which one impacts the other varies. For example, the stakeholder engagement lens is most critical when dealing with performance issues around depth of impact—if the appropriate constituents are not successfully engaged in your organization’s activities, deeper impact is less likely to occur. Stakeholder engagement is also critical to achieving blended value creation, though to a lesser extent—an organization could conceivably create blended value without engaging all the necessary stakeholders. Thus, each performance criteria has a primary lens.

The secondary lenses are often where less obvious synergies and tensions exist. As much as a performance criterion is unlikely to be achieved without a strong focus on its primary lens, it is also likely that when performance does not reach its expected level based on activities in the primary lens, the culprit can be found by examining tensions or lack of synergies in the secondary lenses.

The table can be read two different ways: not only by looking at a given performance criteria across the four lenses (across a row) but also by looking at a given lens across the four performance criteria (down a column). Again, each lens will be primary for a given criteria, and again tensions and synergies will exist in its relationships with the other criteria.

The table brings to our attention the full extent of the integrated approach:

- At a macro level, practitioners manage synergies and tensions between sustainability and social impact in the social enterprise. This view is represented by the time-tested, albeit simplistic, social enterprise adage, “balancing the double bottom line.”

- Upon deeper analysis, however, it becomes apparent that instead of a “double bottom line,” practitioners actually have to coordinate, manage and balance their efforts around (at least) four (and possibly more) performance criteria: depth of impact, blended value, efficiency and adaptability.

- Examining further, we observe that to achieve performance outcomes as per each performance criterion, practitioners’ efforts involve decision making and managing several activities related to each of the four strategic lenses: stakeholder engagement, resource mobilization, knowledge development and culture management.

- Finally, since each strategic lens is seen as playing a role in each performance criterion, the opportunity exists for many more synergies and tensions to be managed within and between the lenses themselves as they pertain to the different performance criteria and influence performance outcomes.

Table 1: Performance criteria accross the four lenses

Table 1: Performance criteria accross the four lensesThis version of the table shows performance criteria across, with the lenses in column.

The content however is absolutely identical to table 2.

Click on any link below to expand the particular cell.

Core Practices:

- Integrate social stakeholders into mainstream markets.

- Integrate market players into social sector.

- Increase interaction and dependence among all stakeholder groups.

- Influence market player behaviors.

Synergies:

- Use stakeholders as resources.

- Seek resources that facilitate or enhance stakeholder engagement.

- Become part of the mainstream market.

Tensions:

- Stay away from resources that hinder stakeholder engagement.

- One-size-fits-all resource requirements hinder access to poorer clients.

Synergies:

- Use market research to further understand root causes of social problem.

- Develop technology appropriate to social context.

- Develop processes that support the use of sustainable resources.

Tensions:

- One-size-fits-all technology can limit access to harder-to-reach clients.

- Risk of falling for the innovation smokescreen (“new is better”).

Synergies:

- Change perceptions about who the stakeholders are.

- Engage mainstream market channels to blur the lines between stakeholder groups.

- Use social marketing techniques to counter damaging marketing messages.

Tensions:

- Excessive use of business jargon might alienate your core stakeholders

Synergies:

- Capture stakeholders' spending power.

- Engage donors in a longer-term investment approach.

- Use stakeholders to diversify human resources.

Tensions:

- Be mindful that increased integration might forfeit traditional fundraising channels.

- Engaging in market mechanisms means less time for traditional fundraising.

Core Practices:

- Retain market wealth-creation at the source.

- Turn social challenges into wealth-creation opportunities.

- Make resources more scalable and renewable.

Synergies:

- Use market research to improve knowledge of resource availability.

- Develop appropriate technology to manage resources renewably.

- Research the potential of less coveted/more available resources.

Tensions:

- Be wary of over promising and under delivering.

- Research requires upfront investments and associated financial risks.

Synergies:

- Promote a culture of self-worth among social clients.

- Be honest about successes and failures when promoting risk-taking.

Tensions:

- New business culture might cause the loss of existing human resources.

Synergies:

- Leverage stakeholders’ knowledge and skills by promoting the concept of “user-led innovation”.

Tensions:

- Increasing stakeholder engagement required accepting slower stakeholder-driven trial and error processes.

Synergies:

- Mobilize resources that directly support knowledge development.

- Use valuation techniques to account for the hidden costs of resources.

Tensions:

- Those not wanting to support development costs are not suited for innovation.

Core Practices:

- Development of appropriate technology.

- Conduct a down-market needs analysis.

- Develop more efficient supply chain models.

Synergies:

- Promote work ethic among social clients and internal stakeholders.

- Promote a mindset in support of knowledge sharing.

Tensions:

- Be mindful of the fact that promoting a more competitive business attitude might impede efforts to promote knowledge sharing.

Synergies:

- Engage stakeholders in devising a coherent shared value system.

- Use stakeholder choice as an adaptability mechanism.

- Use a distributed approach that support grassroots innovation.

Tensions:

- Be mindful not to create a culture in which traditional social work is seen as a dead-end, undermining social staff morale.

Synergies:

- Take into consideration the inherently restricted nature of particular resources.

- Increase your focus on client needs instead of funder needs.

Tensions:

- Be aware that increased requirements for financial returns might have a counter-effect on building a more flexible culture.

Synergies:

- Conduct ongoing market research to inform responses to emerging trends and opportunities.

- Use business performance monitoring and information management practices to improve risk analysis and implementation strategies.

Tensions:

- Be aware that temporary setbacks and risks inherent to the “trial and error” process central to research and innovation will trigger pressure to come back to a low-risk, more predicable charity mindset.

Core Practices:

- Encourage a more competitive organizational environment to increase watchfulness and reduce resistance to change.

- Implement results-oriented, decentralized management practices to support creativity and initiative.

Table 2: Four lenses accross the performance criteria

Table 2: Four lenses accross the performance criteriaThis version of the table shows lenses across, with the performance criteria in column.

The content however is absolutely identical to table 1.

Click on any link below to expand the particular cell.

Core Practices:

- Integrate social stakeholders into mainstream markets.

- Integrate market players into social sector.

- Increase interaction and dependence among all stakeholder groups.

- Influence market player behaviors.

Synergies:

- Capture stakeholders' spending power.

- Engage donors in a longer-term investment approach.

- Use stakeholders to diversify human resources.

Tensions:

- Be mindful that increased integration might forfeit traditional fundraising channels.

- Engaging in market mechanisms means less time for traditional fundraising.

Synergies:

- Leverage stakeholders’ knowledge and skills by promoting the concept of “user-led innovation”.

Tensions:

- Increasing stakeholder engagement required accepting slower stakeholder-driven trial and error processes.

Synergies:

- Engage stakeholders in devising a coherent shared value system.

- Use stakeholder choice as an adaptability mechanism.

- Use a distributed approach that support grassroots innovation.

Tensions:

- Be mindful not to create a culture in which traditional social work is seen as a dead-end, undermining social staff morale.

Synergies:

- Use stakeholders as resources.

- Seek resources that facilitate or enhance stakeholder engagement.

- Become part of the mainstream market.

Tensions:

- Stay away from resources that hinder stakeholder engagement.

- One-size-fits-all resource requirements hinder access to poorer clients.

Core Practices:

- Retain market wealth-creation at the source.

- Turn social challenges into wealth-creation opportunities.

- Make resources more scalable and renewable.

Synergies:

- Mobilize resources that directly support knowledge development.

- Use valuation techniques to account for the hidden costs of resources.

Tensions:

- Those not wanting to support development costs are not suited for innovation.

Synergies:

- Take into consideration the inherently restricted nature of particular resources.

- Increase your focus on client needs instead of funder needs.

Tensions:

- Be aware that increased requirements for financial returns might have a counter-effect on building a more flexible culture.

Synergies:

- Use market research to further understand root causes of social problem.

- Develop technology appropriate to social context.

- Develop processes that support the use of sustainable resources.

Tensions:

- One-size-fits-all technology can limit access to harder-to-reach clients.

- Risk of falling for the innovation smokescreen (“new is better”).

Synergies:

- Use market research to improve knowledge of resource availability.

- Develop appropriate technology to manage resources renewably.

- Research the potential of less coveted/more available resources.

Tensions:

- Be wary of over promising and under delivering.

- Research requires upfront investments and associated financial risks.

Core Practices:

- Development of appropriate technology.

- Conduct a down-market needs analysis.

- Develop more efficient supply chain models.

Synergies:

- Conduct ongoing market research to inform responses to emerging trends and opportunities.

- Use business performance monitoring and information management practices to improve risk analysis and implementation strategies.

Tensions:

- Be aware that temporary setbacks and risks inherent to the “trial and error” process central to research and innovation will trigger pressure to come back to a low-risk, more predicable charity mindset.

Synergies:

- Change perceptions about who the stakeholders are.

- Engage mainstream market channels to blur the lines between stakeholder groups.

- Use social marketing techniques to counter damaging marketing messages.

Tensions:

- Excessive use of business jargon might alienate your core stakeholders

Synergies:

- Promote a culture of self-worth among social clients.

- Be honest about successes and failures when promoting risk-taking.

Tensions:

- New business culture might cause the loss of existing human resources.

Synergies:

- Promote work ethic among social clients and internal stakeholders.

- Promote a mindset in support of knowledge sharing.

Tensions:

- Be mindful of the fact that promoting a more competitive business attitude might impede efforts to promote knowledge sharing.

Core Practices:

- Encourage a more competitive organizational environment to increase watchfulness and reduce resistance to change.

- Implement results-oriented, decentralized management practices to support creativity and initiative.

Depth of Impact

Depth of ImpactEngaging Stakeholders to Achieve Deeper Impact

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Deeper ImpactCore Practices:

- Integrate traditional social stakeholders into mainstream markets by engaging them as employees and consumers.

- Integrate traditional market stakeholders into the social sector, engaging them in changing market behaviors toward solving a social problem.

- Increase interaction and dependence among all stakeholder groups by engaging them through integrated market mechanisms.

- Influence market player behaviors by developing socially responsible markets (making it possible for others to do well by doing good) or hindering socially damaging markets (making it more difficult for others to do well by behaving badly).

Managing Culture to Achieve Deeper Impact

Managing Culture to Achieve Deeper ImpactSynergies:

- Leverage market channels to change perceptions about who the stakeholders are (not just the social clients, but also market players as stakeholders), as well as their roles and responsibilities in solving the targeted social problem, thus reducing the dichotomy between donor and recipient.

- Engage mainstream market channels to blur the lines between stakeholder groups, changing a culture of "us=mainstream" versus "them=fringe" into a culture of "all of us in it together."

- Use social marketing techniques to counter damaging marketing messages that exploit either socially disadvantaged consumers or socially conscious consumers.

Tensions:

- Be wary of excessive use of business jargon as it might alienate your core stakeholders

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Deeper Impact

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Deeper ImpactSynergies:

- Promote resource mobilization strategies that inherently increase stakeholder engagement (e.g. volunteerism instead of financial donation; or charging a fee-for-service to increase commitment and value perception).

- Seek resources that facilitate or enhance stakeholder engagement (e.g. access to communication infrastructure, prime retail location).

- Become part of the mainstream consumer, business and investment community in order to engage them in becoming stakeholders in your social problem.

Tensions:

- Divest or stay away from resources that risk hindering stakeholder engagement (e.g. sponsorship from some corporations might alienate social stakeholders; some public funding might unduly restrict interacting with market stakeholders).

- Be wary of a one-size-fits-all resource mobilization strategy (e.g. charging a fee-for-service across the board) as it might prevent poorer clients from being served.

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Deeper Impact

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Deeper ImpactSynergies:

- Employ market research to deepen our understanding of social clients' needs and wants as well as mainstream market players' roles and responsibilities in perpetuating and solving the social problem.

- Leverage R&D activities to develop appropriate technology that better fits social clients' abilities, needs and wants (e.g. development of specialized equipment).

- Leverage R&D activities to develop mainstream processes that support the use of mission-strengthening resources (use of eco-renewable resources, social clients as workforce, etc.).

Tensions:

- Be wary of one-size-fits-all streamlined technology solutions as they might prevent harder-to-reach clients from being served.

- Be vigilant not to fall for the innovation smokescreen (“new is better”) while failing to take your core stakeholders along with you.

Blended Value

Blended ValueMobilizing Resources to Achieve Blended Value

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Blended ValueCore Practices:

- Use market mechanisms to retain market wealth-creation at the source and use it to solve social problems caused by market failures.

- Use market mechanisms to turn social challenges into wealth-creation opportunities.

- Use market mechanisms to make resources more scalable and renewable in solving social problems.

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Blended Value

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Blended ValueSynergies:

- Use market research methodology to better understand where resources are, how to access them, who controls them, and how valuable they are to others.

- Research and develop appropriate technology to manage available resources (whether physical, human, relational or financial) in a more renewable manner.

- Instead of competing for the most obvious resources, research the potential of less obvious resources (e.g. intellectual property) or readily-available resources traditionally considered less practical (e.g. an efficient way to use volunteers on a larger scale).

Tensions:

- Be wary of over promising and under delivering! Make sure to invest in building knowledge and capacity to fully leverage new resources coming your way and keep up with the unusual (to you) expectations of new resource providers.

- Be mindful of the fact that research and innovation does require upfront investments, and thus always carries some risk of financial loss.

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Blended Value

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Blended ValueSynergies:

- Reach stakeholder groups through market mechanism and capture some of their spending power.

- Engage social sector donors and social investors in a longer-term market investment approach.

- Use your stakeholders to diversify your pool of human resources (social clients might have marketable skills, board members might have business relations, etc.).

Tensions:

- Be mindful that integrating stakeholders along the socio-economic spectrum, although beneficial in reducing social exclusion, also means forfeiting traditional fundraising practices that require marked socio-economic barriers to remain in place (e.g. traditional charity requires a reinforced sense of exclusion).

- Be mindful that engaging stakeholders through market mechanisms also means less time for traditional fundraising, which can be particularly difficult when transitioning from pure nonprofit to social enterprise.

Managing Culture to Achieve Blended Value

Managing Culture to Achieve Blended ValueSynergies:

- Put your social clients to work to promote a culture of self-worth so that they become aware that they can be a resource, not just a burden.

- Be honest about your successes and failures in promoting a risk-taking mindset in which it is acceptable to invest resources toward a potential for sustainable impact instead of distributing resources for risk-free but limited and unsustainable relief.

Tensions:

- Be aware that a business culture might be seen as inappropriate by some, causing the loss of valuable resources in the form of experienced staff and board members.

Efficiency

EfficiencyDeveloping Knowledge to Achieve Greater Efficiency

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Greater EfficiencyCore Practices:

- Implement R&D efforts to increase productivity and reduce costs through development of appropriate technology.

- Use and expand market research methods to conduct a down-market needs analysis.

- Employ market research and business planning activities to develop more efficient supply chain models.

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Greater Efficiency

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Greater EfficiencySynergies:

- Mobilize resources that directly support knowledge development (e.g. access to R&D facilities, intellectual property rights, skilled professionals).

- Use and expand business valuation practices better to take into account the hidden costs of resources (e.g. "free" resources might be inefficient because expensive to maintain, etc.).

Tensions:

- Be wary of resource providers who want to pay for implementing solutions without bearing the development cost; they might be fine to support scaling of existing well-tested activities, not development of new innovative ones.

Managing Culture to Achieve Greater Efficiency

Managing Culture to Achieve Greater EfficiencySynergies:

- Promote work ethic among social clients and internal stakeholders.

- Promote a mindset in support of knowledge sharing.

Tensions:

- Be mindful of the fact that promoting a more competitive business attitude might impede efforts to promote knowledge sharing.

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Greater Efficiency

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Greater EfficiencySynergies:

- Leverage stakeholders’ knowledge and skills by promoting the concept of “user-led innovation,” that is giving stakeholders the right and ability to innovate at the grassroots level in order to benefit from your stakeholders’ unique mix of skills and knowledge.

Tensions:

- Be mindful than promoting greater stakeholder engagement might require limiting top-bottom interventions in process development, at times taking a more circuitous route involving stakeholder-driven trial and error processes.

Adaptability

AdaptabilityManaging Culture to Achieve Greater Adaptability

Managing Culture to Achieve Greater AdaptabilityCore Practices:

- Encourage a more competitive organizational environment to increase watchfulness and reduce resistance to change, especially when change creates opportunities for increased performance and impact in line with a changing environment.

- Implement results-oriented, decentralized management practices to support creativity and initiative.

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Greater Adaptability

Engaging Stakeholders to Achieve Greater AdaptabilitySynergies:

- Engage stakeholders in devising a coherent value system that works for all and reduces exclusion.

- Use stakeholder choice as an adaptability mechanism, similar to how consumer choice plays an important role in setting market trends.

- Instead of a top-down approach to addressing a social problem, use a distributed approach that seeks to provide products and services that support additional grassroots innovation (e.g. providing modular solutions that can be customized at the local level).

Tensions:

- Be mindful not to engage some stakeholders while overlooking others, creating a culture in which the social enterprise activity is seen as “the place to be” while traditional social work is seen as a dead-end, undermining social staff morale.

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Greater Adaptability

Developing Knowledge to Achieve Greater AdaptabilitySynergies:

- Conduct ongoing market research to inform responses to emerging trends and opportunities.

- Use business performance monitoring and information management practices to improve risk analysis and implementation strategies.

Tensions:

- Be aware that temporary setbacks and risks inherent to the “trial and error” process central to research and innovation will trigger pressure to come back to a low-risk, more predicable charity mindset.

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Greater Adaptability

Mobilizing Resources to Achieve Greater AdaptabilitySynergies:

- Devise a resource mobilization strategy that takes into consideration the inherently restricted nature of particular resources (e.g. restrictions from grant funding vs. earned income).

- Leverage your reduced focus on traditional fundraising to increase your focus on client needs instead of funder needs.

Tensions:

- Be aware that increased requirements for financial returns might have a counter-effect on building a more flexible culture; replacing one set of inflexible requirements (expected changes in social indicators) by another one (expected changes in financial criteria ) will do nothing to solve flexibility problems.

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder EngagementResource Mobilization

Resource MobilizationKnowledge Development

Knowledge DevelopmentCulture Management

Culture ManagementConclusion

ConclusionThe strength of the Four Lenses Strategic Framework is that it reveals inherently greater complexity in social enterprise operations, management, and strategic decision making than what has been addressed to date in social enterprise methodology or the literature. Like an onion, the framework peels back layers, exposing deeper and deeper levels of dynamics within the social enterprise that must be managed internally while simultaneously managing interactions with a changing external environment.

Overall, practitioners are concerned with managing synergies and tensions between sustainability and social impact. This “big picture” image of a social enterprise’s broadest goals is often depicted with a scale showing social impact on one side and sustainability on the other. Beneath the so-called “double bottom line,” the next level of performance indicates that rather than simply gunning for impact and sustainability, practitioners must coordinate, manage and balance their efforts around four measures of performance: depth of impact, blended value, efficiency and adaptability.

The next layer of analysis in the framework demonstrates that to achieve performance outcomes, practitioners must scrutinize performance criteria through four different strategic perspectives: stakeholder engagement, resource mobilization, knowledge development and culture management.

At the final level the framework examines synergies and tensions that occur within each strategic lens as well as between lenses that effect performance outcomes. Here, the framework illuminates that performance is continually challenged in the complex world of the social enterprise, and as a result practitioner decisions often entail operational tradeoffs and concessions in order to achieve strategic performance objectives.

In conclusion, the Four Lenses Strategic Framework is an attempt to offer a model that accounts for the complexity of the social enterprise and lays the groundwork for a comprehensive performance methodology. While the framework integrates social enterprise best practices from various schools of thought, it shuns simple dualistic views of the black and white social enterprise. Instead, its unique and essential contribution to contemporary performance methodology is its holistic examination of the social enterprise. In doing so, the framework regards social enterprise performance as the aggregate of a complex network of internal systems that function individually as well as interdependently to achieve a high performing whole.

For a social enterprise to be successful, internal systems must be impeccably managed and maintained along with their often subtle, multifaceted, and inextricably linked mutually-dependent relationships with one another. Moreover, this complex internal environment of the social enterprise must be managed against the backdrop of a dynamic market environment. Thus the framework serves to navigate practitioners through an intricate and potentially delicate strategic and management decision making process, which includes assessing ramifications of certain decisions on performance and social enterprise operations.

The aim is that social enterprise practitioners will use the framework as a mainstay to assess performance, inform strategic decision making, and direct routine management in order to achieve the desired results of sustainable social impact. In its current form, the framework is a flexible tool for analysis that can be used to assess and measure how well a social enterprise is performing vis-à-vis its targets, and it can also be incorporated into strategic planning exercises. We fully expect the Four Lenses Strategic Framework to change and evolve over time, spurring new and more robust applications and simpler tools. At this point, the most critical element toward strengthening the Four Lenses Strategic Framework is to engage practitioners in its development. The hope is that this framework provides adequate common ground around challenges and performance criteria to convene a discussion about performance among an extremely heterogonous audience of social enterprise practitioners.

We believe that the promise of social enterprise is twofold: not only does social enterprise offers new ways of tackling age old social problems, but it also offers a new paradigm for social organizations to improve their effectiveness. The purpose of this framework is to support the social enterprise community by developing an integrated performance methodology to help practitioners achieve efficient, adaptive, strategically-minded organizations capable of simultaneously creating economic wealth and social value and addressing root causes of social problems in order to achieve deep, lasting social impact.

Research Methodology

Research MethodologyThe departure for this research was the authors' reaction to the lack of literature on social enterprise performance analysis and methodology. The other key impetus was the absence of practitioner participation in flagship exercises to define social enterprise and set an agenda for the field (these were largely dominated by funders and academics). Consequently, all primary research for the Four Lenses Strategic Framework came directly from social enterprise practitioners.

The authors used a combination of 'bottom up' action research that actively engaged practitioners in assessing social enterprise performance and analyzing information needs; defining performance criteria and strategic lenses; giving feedback on the performance process and application of the methodology; and providing examples. Through partnerships with social enterprise support intermediaries (Great Bay Foundation, PACT, SEEP and CARE), the authors sponsored several surveys and focus groups and conducted personal interviews. Extensive field research was undertaken to apply the framework and then to develop the cases in the US, India, Tanzania and Kenya.

The research was intended to build a practice-to-theory model for social enterprise performance. Thus, save for advisory board members' involvement to plan the process, rudder the research, and to critique products, all research was drawn directly from practice.

The Authors

The AuthorsVincent Dawans is Partner of Virtue Ventures LLC (www.virtueventures.com), a management consulting organization focused on advancing social enterprise methodology and practice. Vincent conceived the Four Lenses framework and championed this project. He can be reached via the contact form.

Kim Alter is Managing Director and Founder of Virtue Ventures LLC (www.virtueventures.com). Kim gathered much of the primary research from practitioners to inform this framework as well as helping to pen it. She is also a Visiting Fellow at the Skoll Centre of Social Entrepreneurship at Said Business School University of Oxford, and is author of several works on social enterprise.

Lindsay Miller is an Associate at Virtue Ventures. Lindsay is responsible for much of the case writing accompanying the framework. She is also an Oxford MBA graduate and Skoll scholarship for social entrepreneurship recipient.

Acknowledgements

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank and acknowledge all those who helped to make this work possible.

First and foremost, tremendous gratitude is owed to the Skoll Foundation, for its very generous grant to underwrite this paper and our larger field building project.

Very special thanks to CARE Enterprise Partners for making the first commitment toward developing seToolbelt (www.setoolbelt.org), a free open source resource library for social enterprise practitioners.

Appreciation goes to The SEEP Network for supporting an international social enterprise practitioner working group pilot, online conference, and several information meetings and events at its annual conferences (2007-08).

We are grateful to the Great Bay Foundation for corralling their grantees for workshops, focus groups, and surveys, and generally allowing us to use them as 'guinea pigs' from which to gather primary research and test our concepts.

We appreciate contributions and support from Social-Impact to support development of Industree and MARI case studies as well as to the Philippson Foundation for its support of the APOPO case.

A mention is also owed to the Grassroots Business Initiative/IFC for sponsoring a special lunch meeting of social enterprise practitioners in economic development.

Considerable recognition goes to Christian Pennotti for writing the case study on MARI in India. It should be noted that Christian also helped develop the case study research questions, provided feedback on the early framework, and was the first to test the framework in the field.

Last, but by no means least, a very special thanks is owed to all social enterprise practitioners from Great Bay Foundation, The SEEP Network, Social Impact, UnltdWorld, Skoll World Forum and others that were instrumental in contributing to the development of the framework and other products for this project.

Project Advisors are owed immense gratitude for their guidance and advice, and moreover supporting the project long before we received funding. Each one is a respected leader and major contributor to social enterprise; their thoughts, ideas, words, and previous work laid the foundation for this piece.

- Beth Anderson, Former Lecturer and Managing Director, Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship (CASE) Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business

- Evan Bloom, Former Director of Capacity Building Services Group, PACT

- Dan Crisafulli, Senior Program Officer, Skoll Foundation

- Greg Dees, Professor of Social Entrepreneurship Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business

- Jimmy Harris, Former Deputy Director, The SEEP Network

- Elizabeth Isele, Director, Great Bay Foundation

- Farouk Jiwa, Founder of Honey Care Africa and Former Director of Private Sector Development, CARE Enterprise Partners, CARE Canada

- Mary McVay, Director of Value Initiative, The SEEP Network

Additional thanks are owed to Tom Davis, Melvin Muriel, Kathy Freund, Maureen Beauregard, Ted Regan, Robert Chambers, Cathy Duffy, Amaan Khalfan, Margaret Mimoh, and numerous other practitioners who provided valuable information and insight for this report. Special recognition goes to Laura Brown who has been our editor for longer than many marriages last. Finally appreciation goes to staff at The Great Bay Foundation and The SEEP Network, namely Sabina Rogers and Travis Cummings, for their support.

Methodology

MethodologyThis case represents the first installment of a case study series developed to test and enhance the “Four Lenses Strategic Framework” as a tool for analyzing organizational behavior and performance in aspiring and established social enterprises.

It is organized around four key performance criteria: Depth of Impact, Blended Value, Efficiency, and Adaptability. These criteria are further examined through four intrinsically linked strategic lenses: Stakeholder Engagement, Resource Mobilization, Knowledge Development, and Culture Management.

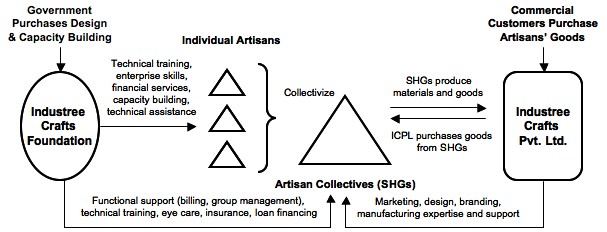

The Four Lenses Strategic Framework is an integrated approach to social enterprise that postulates that high performance is linked to an organization’s activities across the Four Lenses. Building on this premise, the Industree Craft case study describes activities across strategic focus areas and illuminates the synergies and tensions that arise when taking an entrepreneurial approach to addressing a social problem like rural poverty in India. The case study highlights the organization’s many notable strengths, while also illustrating potential implications of Industree’s hybrid structure and its impending scale-up process, the challenges that lie ahead, and the lessons this case holds for similarly structured organizations.

| Performance Criteria | Primary lens through which performance is delivered… | Secondary lenses further enhancing or hindering performance… | Depth of Impact | How successful are we at engaging all stakeholders deeply and durably? | How do our culture, resources and knowledge support (or hinder) a deeper stakeholder engagement? |

|---|---|---|

| Blended Value | How successful are we at mobilizing resources in an integrated, viable and renewable manner? | How do our knowledge, stakeholders and culture support (or hinder) viable resource mobilization? |

| Efficiency | How successful are we at developing knowledge that leads to more appropriate processes? | How do our resources, culture and stakeholders support (or hinder) the development of appropriate processes? |

| Adaptability | How successful are we at creating a culture that supports initiative and reduces resistance to change? | How do our stakeholders knowledge and resources support (or hinder) a culture of change and initiative? |

This case was developed through an extensive documentation review, electronic correspondence, and a series of in-person interviews with Industree’s Founders, Neelam Chhiber and Gita Ram, top management (including Industree’s CEO, R. Singh Rekhi), other Industree employees, stakeholders, and rural artisan groups. Information for the case was also gathered by way of Neelam Chhiber’s participation in Social-Impact International, a professional development and support accelerator for social entrepreneurs in India. With the support of Social-Impact’s one-year program, Chhiber fine-tuned Industree’s incorporation of social enterprise methodology and launched the scale-up plan described in this case study.

Acknowledgements

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank Industree Craft founders, Neelam Chhiber and Gita Ram, and all the Industree staff for their generous accommodation throughout the research process for this case. Much gratitude is owed to Social-Impact for first sponsoring the work of Industree and other social entrepreneurs in India, and second, for their financial contribution to documenting this case. Finally, many thanks go to the Skoll Foundation for supporting the development of the Four Lenses Strategic Framework, this and other cases, and the tools and resources that accompany the Framework. The field of social enterprise will continue to strengthen and evolve as a result of the Skoll Foundation’s commitment to capacity-building initiatives like the Four Lenses.

Introduction

IntroductionThere are some 40 million rural artisans in India today. While global demand for Indian artisan products is growing both in India and abroad, rural artisans largely remain poor. Prior to the industrial revolution, high quality artisan products were historically crafted in rural areas for domestic and international consumption. Following the economic reforms of the 1990s, the government’s heightened support for manufacturing centers in urban hubs has increasingly isolated rural producers and decreased their access to functioning markets. As a result, much of India’s rural population has migrated to cities in search of work, sadly trading rural unemployment for urban displacement and poverty.1

At the same time, India has seen substantial shifts in its domestic marketplace, with trends projected to continue. The country has emerged as a global economic force, with its growing middle class becoming an increasingly upwardly mobile population. Economists estimate that 320 million additional people will join the consuming class by 2010, and organized retail, reaching $25 billion in 2007-08, is estimated to quadruple by 2010. A new generation of socially responsible consumers is emerging in India’s urban centers, one that is rooted in ethnicity yet aspires to modernity. One Indian organization is addressing this gap between rural unemployment, traditional artisan craft, and India’s growing consumer market.